| Previous Page |

PCLinuxOS Magazine |

PCLinuxOS |

Article List |

Disclaimer |

Next Page |

Making Quality Music Easily & Cheaply On PCLinuxOS, Part 1 |

by Agent Smith (Alessandro Ebersol)

So, friends, have you always wanted to make music on your computer? But you didn't have that overrated word called talent? Or, you never learned music theory, and so you think you can't produce anything? Or worse, making music on the computer will be an expensive investment, requiring expensive and specific equipment… Well, friends, if you think all that, this article is for you. Making music today requires neither practice nor skill: even a child can do it. And what's better, it will sound good every time you learn more and more about this fascinating subject that is music in modules and trackers.

Making music nowadays has become very easy. Websites such as Suno, Udio, and Eleven Labs allow you to “create” music with generative AI, and it actually sounds pretty good. But what I propose here is a different approach: how to create digital music on your computer running PCLinuxOS, with programs that are in the PCLinuxOS repositories. Well, what led me to do this? I've always liked modular music, and I've heard incredible compositions and recreations with this type of music, and, of course, deep down, anyone who likes to listen would also like to make their own music. Of course, not knowing ANYTHING about music theory can get in the way, but things aren't quite like that. A lot of hip-hop stars know nothing about music and just use autotune and software-generated compositions, with drum machines and everything else. So don't feel so bad. Now, one inspiration for me was knowing that one of my idols knew nothing about music theory, and that didn't stop him from making the most beautiful and legendary songs ever heard.

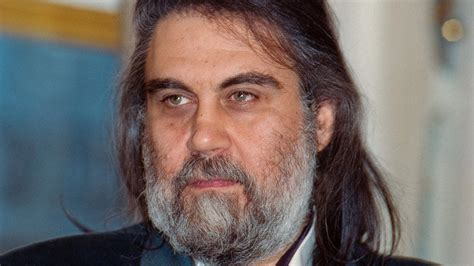

Evángelos Odysséas Papathanassíu, the real name of the artist Vangelis, who died in 2022 at the age of 79, was a legend of electronic music and knew nothing about music theory. Yes, he composed by ear, but that didn't make his songs any less legendary: the soundtracks for the films Blade Runner and 1492, not to mention all his solo work and the creation of the group Aphrodite's Child, with singer Demis Roussos, among others. Of course, over time, he learned and improved his relationship with theory. And, obviously, his results were much better than some hip-hop singers with autotune. So, we arrive at that moment when we conclude: If he can do it, why can't we? And we can make music without spending a lot and without knowing much either… After all, the important thing is to have an open mind and curiosity. Before we begin, a disclaimer: I don't understand music theory, and what I learned was by playing around with the programs. I still don't know how to compose a song, but I've already started making some noise with the programs in the PCLOS repositories. One more note: I packaged all the modular music composition programs, the trackers, myself.

To understand what module music is, we need to go back in time, about 39 years, and analyze one of the best computers ever created: the Commodore Amiga.

Commodore Amiga was a line of computers manufactured by the Canadian company Commodore, which, to this day, I think, was greatly underestimated. To give you an idea (the younger ones, the old guard lived through this, and so did I), in 1985, Amiga was already doing things that Apple and IBM PC platforms would only do 10 to 15 years later. Graphics with 4096 colors on the screen? Yes! PCM sound processor? Yes! Video editing and superimpose capabilities? Yes! Many TV series and stations used the Amiga for visual effects (the series Babylon 5) and video editing, with Video Toaster. And audio production on the Amiga was possible thanks to its revolutionary chipset for the time.

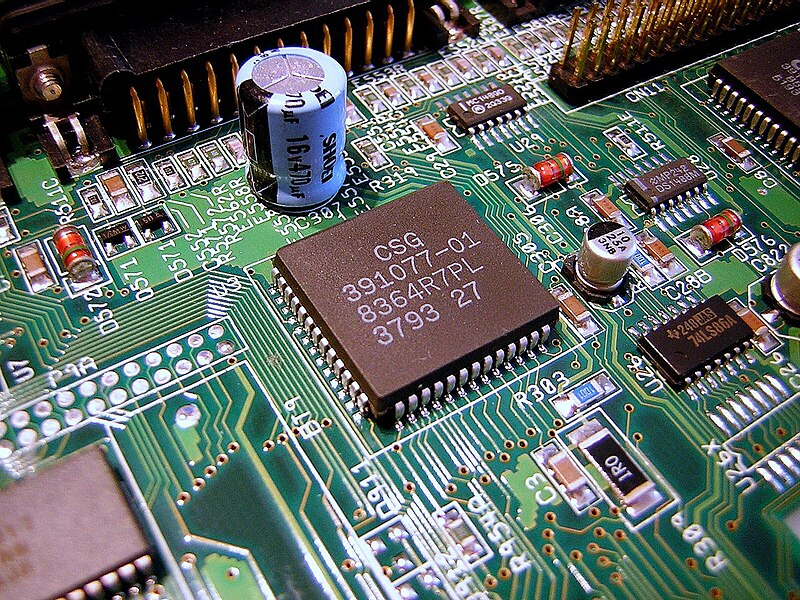

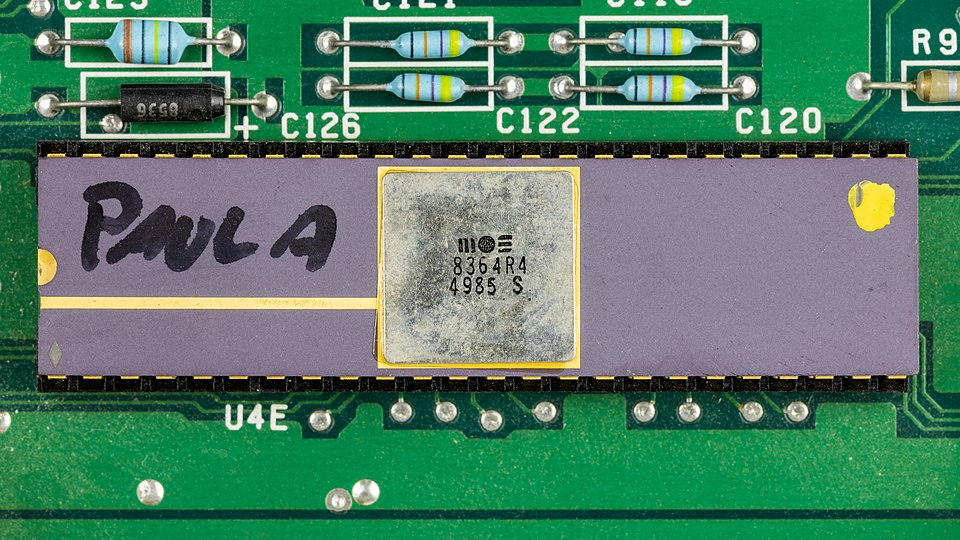

The original architecture of the Amiga, its primary specification, consisted of three custom chips: Agnus, Denise, and Paula are the custom chips used in the first Commodore Amiga computers. They formed a specialized multiprocessor system that took much of the critical load off the main processor. Their functions are as follows:

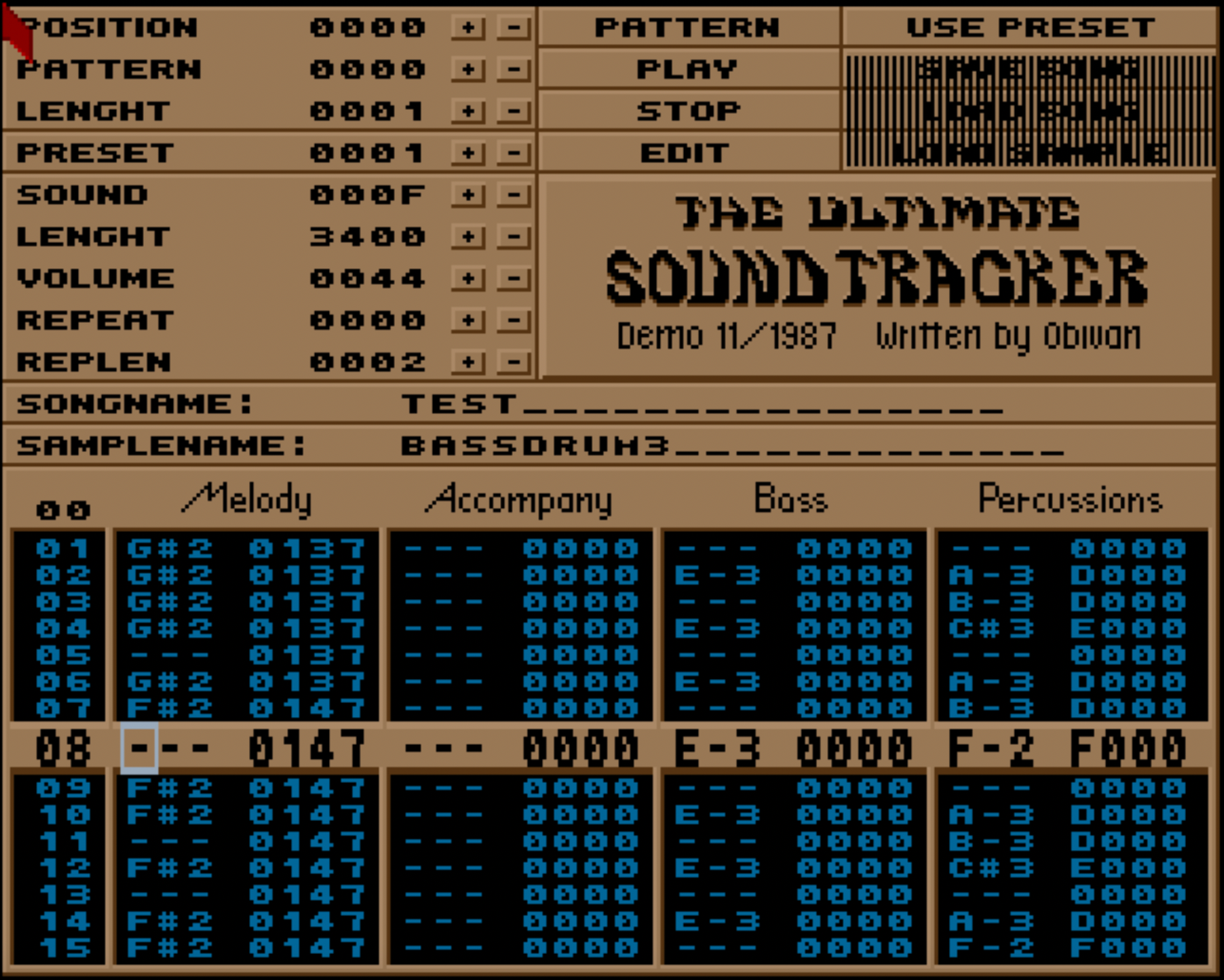

Here, we are interested in the Paula chip. Let's talk about it. Paula, a true Amiga!  As part of the custom chips, Paula was responsible for sound output on the Amiga. It offered four sound channels, each of which could produce samples with 8-bit resolution and 28 kilohertz. It wasn't really CD quality, but it was more than most competing computers could offer. And for comparison: just a few years earlier, you had to pay $25,000 for the Fairlight CMI II digital synthesizer with similar sampling performance. And in 1987, with the advent of the Amiga 1000, everything changed. Karsten Obarski programmed the Ultimate Soundtracker tool for the Amiga 1000 in the summer of 1987 and released it through the German software publisher EAS in December 1987. He was 22 years old. It was the first program he had ever completed. He initially wrote it to compose his first song for the first game by his friend Guido Bartels.

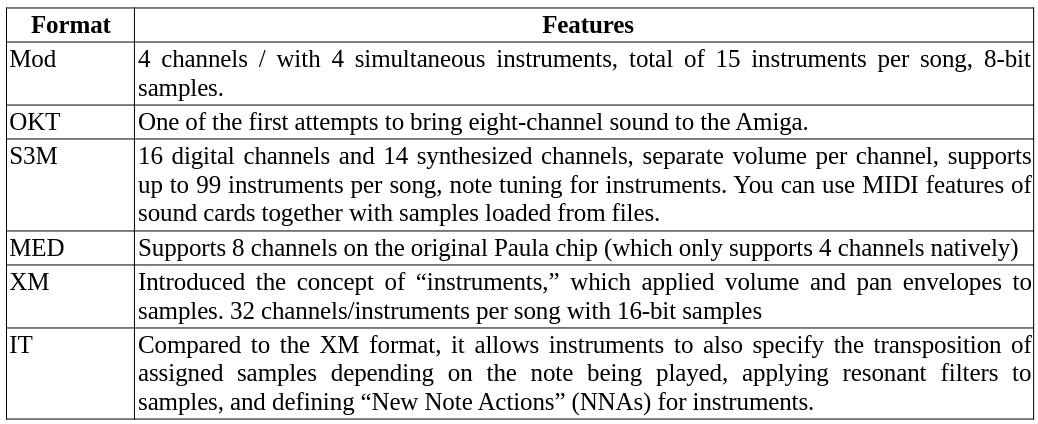

Soundtracker began as a tool for developing sounds for Amiga games. The program allowed four-channel hardware mixing on all Amiga computers, but unlike later versions, it limited the number of samples/instruments in a song to 15. It could export tracks as a sequence of assembly instructions and later introduced its own MOD file format. A disc with instrument samples (ST-01) was distributed along with the program. Soundtracker was released as a commercial product in December 1987. It was not successful as general music development software, with critics calling it “illogical,” “difficult,” and “temperamental”; it was overshadowed in this market by programs such as Aegis' Sonix and Electronic Arts' Deluxe Music Construction Set. In fact, the program was quite buggy and crashed very often, one of the reasons for its failure. However, The Ultimate Soundtracker's interface was groundbreaking and became a standard for game sound production on the Amiga. Despite the problems with the original version, some computer enthusiasts saw its good ideas; the original Ultimate Soundtracker code was quickly reverse-engineered and illegally improved upon, with no regard for Obarski's intellectual property. Soundtracker II was released by The Jungle Command group, followed by a multitude of other illicit versions by various different groups, with numerous improvements over the official, legal commercial version. Modified versions of the program spread throughout the growing Amiga warez scene. Well, now that we've looked at the history of trackers and music modules, let's learn a little about how they work, and get some theory under our belts so we can understand how to use the programs and make some noise with them.

As we have seen, the music module was born on the Amiga in the late 1980s and quickly became an audio standard for this line of computers. So much so that many classic Amiga games use this format (and some classic DOS/Windows games as well, as we will see below). Notable Amiga games that use module music:

Music modules, unlike the MID format, encapsulate an instrument sample and instructions on how to play that sample, producing different notes and varied effects.

The musical notation used by tracker programs is letter notation:

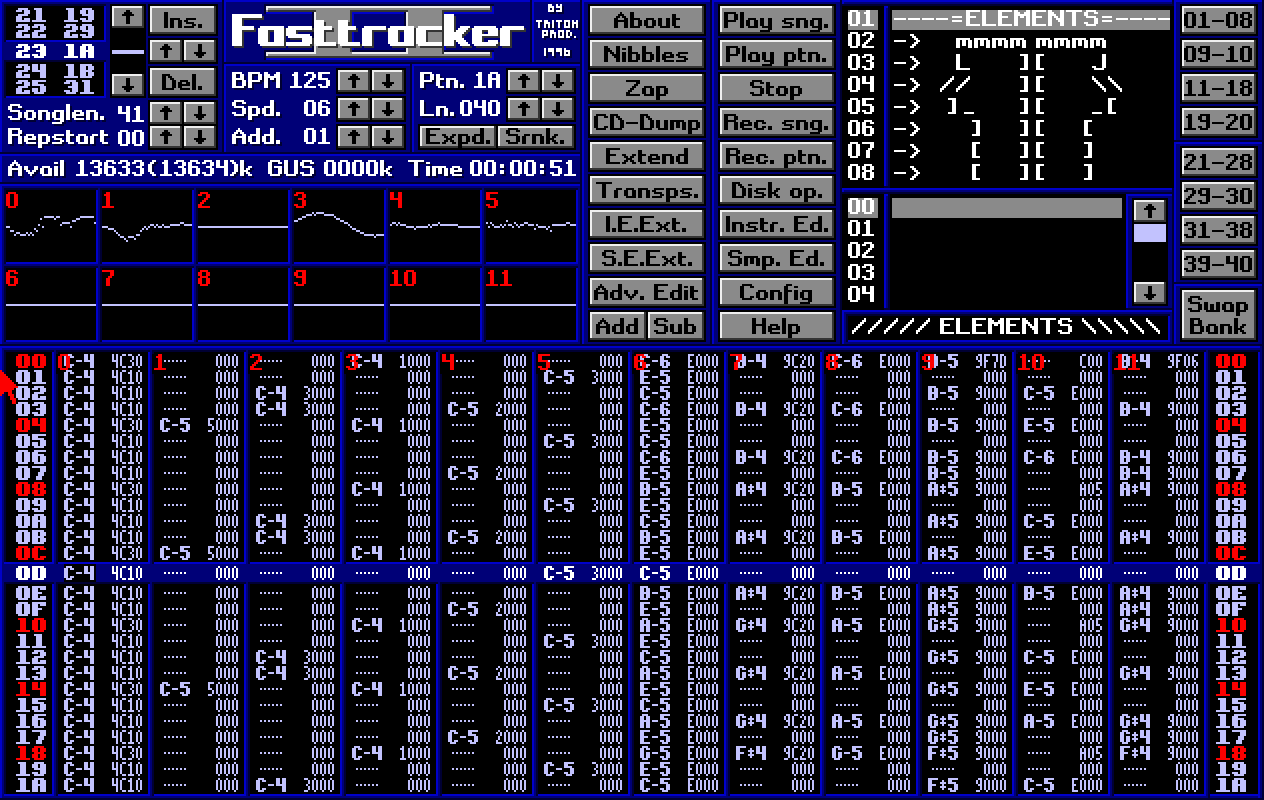

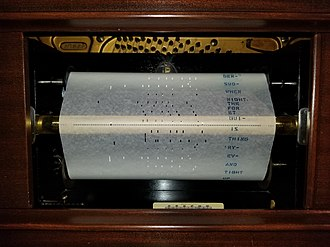

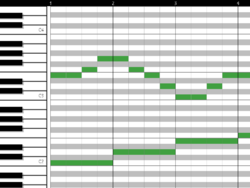

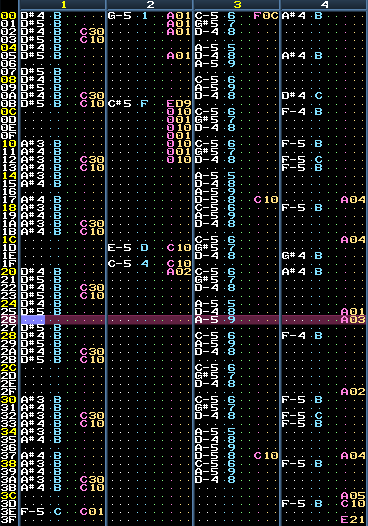

A piano roll is a music storage medium used to operate a mechanical piano, a piano player, or a player piano. Piano rolls, like other music rolls, are continuous rolls of paper with perforated holes. These perforations represent note control data. The roll moves over a reading system known as a tracking bar; the playback cycle for each musical note is triggered when a perforation passes the bar. Piano rolls have been in continuous production since at least 1896 and are still manufactured today, although they are no longer mass-produced. MIDI files have generally replaced piano rolls in the storage and playback of performance data, performing digitally and electronically what piano rolls do mechanically. MIDI editing software often offers the ability to represent music graphically as a piano roll.  A piano roll from a DAW program In the figure above, we see a piano roll from a DAW (Digital Audio Workstation) program that moves from left to right, playing the notes in sequence as they appear in the rows (notes), and the columns are the time axis, representing the passage of time in the performance of the music. In the case of module trackers, the piano roll will work from bottom to top, and each column will be an audio channel where one or more instruments will be played, depending on the type of music module format being played/edited/created.  Piano roll of a 4-channel tracker module, where notes are specified by alphabetic notation So, to create modular music with a soundtracker, you need to indicate which instrument will play on a given channel and at what point it will play that instrument. All tracker programs allow you to control the tempo (how many beats per minute) and, depending on the module music format, can perform various sound effects:

In this series of articles, I will cover the following software (in the PCLinuxOS repositories):

And also OpenMPT software, which is native to Windows but runs perfectly via Wine. Additionally, the Audacity program will also be used to edit instrument samples that we will use in our songs. I hope you enjoyed this introduction, and in the next issues, we will learn how to use soundtrackers to make noise. Until then, I say farewell and be safe. |